That shows the impact a well written article can have. It also points to a change in the mood in America. Since Trump pulled out of the Paris Agreement, happy to risk climate rapture for the quarterly earning of his donors, attention for climate change in America has spiked.

Americans are living through a nightmare, where you see the danger coming, but cannot convince others to stand up to it. Until you wake up bathing in sweat and pick up your phone from the night stand to read tweets from climate "sceptics" mocking you for facing reality. The same people that make a nightmare out of a perfectly solvable problem.

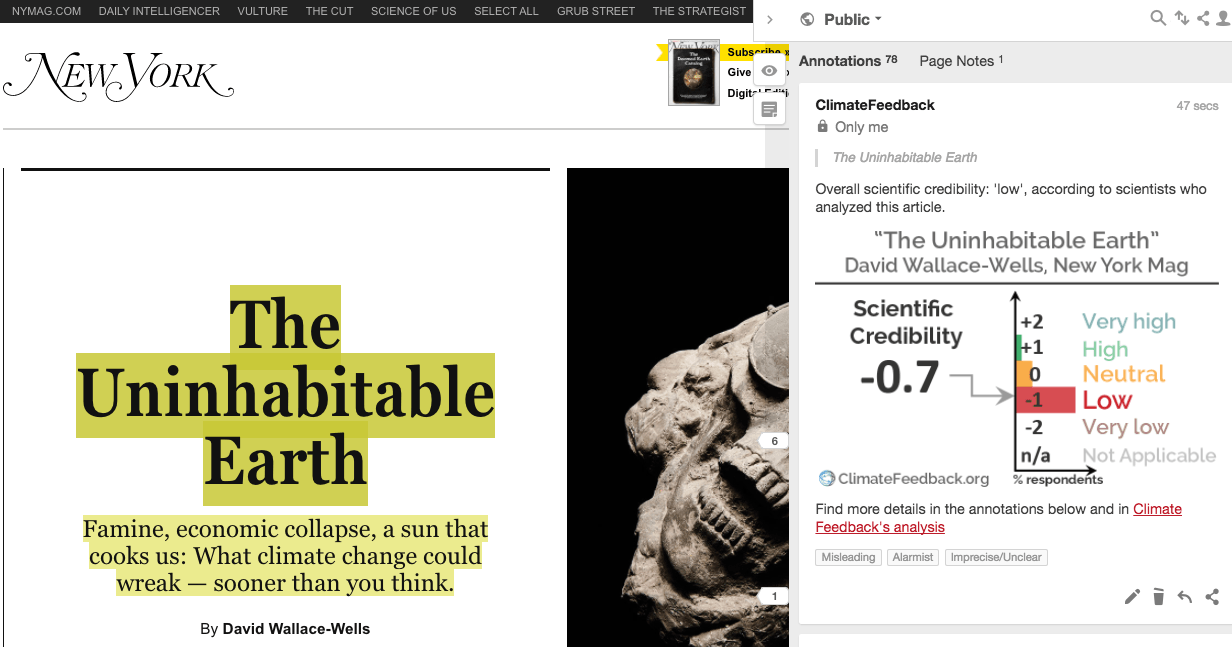

Sixteen climate scientists of Climate Feedback (including me) reviewed the NY Mag article. This number of reviewers may also be a record.

My summary would be that while the dangers of unfettered climate change are real, we found many inaccuracies, which typically exaggerated the problem. Thus the article was rated as having a "low scientific credibility". Both the NY Mag article and the Climate Feedback rating and earlier criticism by Michael Mann have sparked some controversy.

This post will be about how I would prefer the media to report on worse case scenarios. A second post will be about whether our "nitpicking" was the science police striking again?

I have no idea how 2100 looks like. Put yourself in the place of a well-informed citizen of 1900 and what they may have thought today looks like. Meters of horse shit on the streets due to the growth of traffic? Or imagine how an American thought this time would look like 50 years ago. Flying cars and Mars colonies?

Maybe in 2100 humanity has gone extinct, maybe civilization is gone, maybe humans are enslaved by corporations, maybe currently poor countries are also affluent and corporation can no longer repress us, maybe after another century of development we lead wonderful lives, maybe we are building our first intersolar cruiser, maybe no one cares about intersolar cruisers and people impress each other with poetry and four dimensional chess. Very likely they will be painfully embarrassed for me for the options I gave.

I have no idea how they view climate change in 2100. Do they see it as the biggest historical liability put on them? Are they annoyed at the tax burden for the huge necessary geo-engineering program? Do they wonder why people in 2017 thought it was such a big problem, while it was so easy to solve? Are they happy that due to the geo-engineering program they now have weather satellites and it only rains at night in urban areas?

Even in the best case scenario we are taking the climate system out of known territories. There will be many surprises and to be honest those are what worry me the most. The Uncertainty monster is not our friend and that makes it very hard to say which worst case scenarios are unrealistic.

It is custom to accept smaller risks the bigger the stakes are. Cars and smoking kill many people, but one at a time. A risk someone may be willing to take personally will be larger than the risk one takes with a community, a country or our civilization. The risk of dying in a car accident is 1 in 84 (1.2 %), this would be an unacceptable risk for civilization or humanity. Thus we have to look at the tails.

Finally, we expect the impacts of climate change to accelerate: Because some variability is normal, the first degree of warming makes much less problems than the next. Thus the risks of above average warming are expected to contribute much to the total risk. It is thus good that the article explores what surprises may be in store and talks about scenarios that are not likely, but risky.

Four horsemen of the apocalypse

The article reaches the worst case scenarios in four ways:- The worst case for the emissions of greenhouse gases.

- The worst case for how sensitive the climate system responds.

- The worst case for the impacts and how humanity responds.

- The worst case for the scientific assessment of the evidence.

This is the IPCC report from 2013 and the scenarios were created well before that. My impression is that with the [[Paris climate agreement]] and the fast drop in the prices of renewable energy and storage, the RCP8.5 scenario is no longer very realistic. Another optimistic sign is that industrial emissions have stabilized the last 3 years. However, the US mitigation sceptical movement and their president will keep on fighting to make this dystopia a reality. So it is a legitimate question what kind of a world fossil fuel companies and these people want to create.

2. It is completely legitimate to explore the tails of the probability distribution of the climate sensitivity. Even if it had only 30% probability, Trump did get elected. Even if the chance is just one out of six, you sometimes role a six. And let's not start about Russian roulette. Unfortunately the tail of the distribution is not well constrained and very high sensitivities are hard to exclude.

3. The uncertainty of some impacts can be quantified reasonably well. These are the ones with the most physics in them such as heat waves and large-scale increases in precipitation. Then it is legitimate to go into the tail.

Other impacts are not understood well enough yet (Will ice sheets collapse? How much greenhouse gasses will the soil release due to heating?) or will never be fully predictable because of societal and technological influences (Will The Netherlands evacuate before or after Noah's flood? Will plant breeding keep up with climate change? Will societies be able to cope with climate refugees?). In such cases I would like to hear a balanced spectrum of views, including extreme ones.

Because the broad sweeping article discussed many climate change impacts it could not do justice to complexity of individual impacts. Climate change is typically just one stressor of many. When The Netherlands floods, the climate "sceptics" will not suddenly wake up and say "silly me, I was wrong, now I recognize that climate change is a problem, sorry about that". They will say the storm was to blame and it was really bad luck the storm came from the North West and its maximum coincided with high tides, the dikes were not strong enough, the maintenance not good enough and especially the government is to blame.

Looking at history or at the future only from a climate change perspective brings back bad memories of [[climate determinism]]. The Age recently reported on farm workers in Central America suffering and dying from chronic kidney disease. The regions where this new decease happens is well predicted by warming and changes in insolation. Simultaneously the problem is that these people are so poor that they have to work on hot days and also have a strong work ethic that promotes this. They tend not to drink during work and when they do it are often soft drinks because they are perceived as safer. A large part of the problem is funding for preventative care and people die because they cannot afford dialysis.

Among the worst: Ellsworth Huntington's maps of climate 'energy'. But the idea that climate determines society go back to the Greeks 3/10 pic.twitter.com/5sVUmC70Dj— Simon Donner (@simondonner) 13 July 2017

This example shows two things. First of all, like the dikes breaking in The Netherlands, the problem has many aspects. Secondly, this was a problem because it was new. There will be many surprises due to climate change. The study of (rare) diseases helps in understand how a healthy body works. It shows what is important for healthy functioning. Medicine can study many bodies, we only have one Earth and will very likely be surprised what the Earth did for us without us realising it.

4. Like for non-physical impacts, where I am hesitant to go into the tail is when it comes to the interpretation of the evidence. That quickly ends in cherry picking experts that say what you want to hear. Those are strategies for mitigation sceptics. Even if those experts do not stray from the evidence and only hold a pessimistic view; I feel this is not for serious science reporting. It is fine to explain the ideas of such experts, but they should be balanced with other views.

Concluding, for the objective part of the problem: if you clearly say you are looking at the worst case feel free to go deep into the tail of the probability distribution. Only looking at mean changes understates the risks. The tail is a big part of the risk and thus very important. Do not forget to talk about many further surprises and that the Uncertainty Monster has an ugly bite.

When it comes to the more subjective parts, please balance pessimistic with optimistic voices. Subjective judgements are unavoidable when it comes to worst case scenarios and the far future where the changes will be largest. People can legitimately have different world views and as a science nerd I would like to hear the full range of legitimate views.

An article needs a focus, but please consider that climate change is one stressor of many. Climate change impacts are complicated, do them justice like a great novelist would and do not make a cartoon out of them.

Related reading

The updated New York Magazine piece By David Wallace-Wells: The Uninhabitable Earth - Famine, economic collapse, a sun that cooks us: What climate change could wreak — sooner than you think. (The reviewed original, with annotations)The Climate Feedback Feedback: Scientists explain what New York Magazine article on “The Uninhabitable Earth” gets wrong.

New York Magazine now also published extended interviews with the scientists interviewed for the piece: James Hansen, Peter Ward, Walley Broker, Michael Mann, Michael Oppenheimer.

A balanced article in The Atlantic: Are We as Doomed as That New York Magazine Article Says? Why it's so hard to talk about the worst problem in the world.

Michael E. Mann: The ‘Fat Tail’ of Climate Change Risk

Fans of Judith Curry: the uncertainty monster is not your friend

Introduction to Climate Feedback: Climate scientists are now grading climate journalism

Michael E. Mann, Susan Joy Hassol and Tom Toles in the WP: Doomsday scenarios are as harmful as climate change denial. Good people, but I am not buying it: one negative journalistic story in a full media diet does not make people despair, hopeless and paralysed. Plus reality is what it is.

* Painting of the Four Horsemen by Viktor Vasnetsov - http://lj.rossia.org/users/john_petrov/166993.html, Public Domain, Link