The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists that also uncovered the Paradise Paper and Panama Papers investigated the world of predatory scientific journals and conferences. Most of the investigation was done by German journalists, where it has become a major news story that made the evening news.

The problem is much larger than I thought. In Germany it involves about five thousand scientists, about one percent sometimes use these predatory services. That is embarrassing and a waste of money.

While the investigators seem to understand scientific publishing well, it seems they do not understand science and the role of peer review in it. One piece of evidence is the preview picture of the documentary at the top of this article. It shows how the two reporters dressed up to present some nonsense at a fake conference. Presumably dressed up how they think scientists look like. Never seen such weird people at a real conference.

They may naturally claim they dressed like that to make it even more fake. But they also claim that no one in the audience noticed their presentation was fake, I guess they think so because they got a polite applause. That is not a good argument, everyone gets an applause, no matter how bad a presentation was.

A figure from the article that was published in the proceeding of the above fake conference with the title "Highly-Available, Collaborative, Trainable Communication - A Policy-Neutral approach". Clearly no one had a look at it before publishing. It got a "Best Presentation Award".

The stronger evidence that the reporters do not understand the way science works are the highly exaggerated conclusions they draw, which may lead to bad solutions. At the end of the above documentary (in German) the reporter asks: "Was wenn man keinen mehr glauben kann?", "What if you can no longer believe anyone?". Maybe the journalists forgot the ask the interviewed scientists to assess the bigger picture, which is what I will do in this post. There is no reason to doubt our scientific understand of the world because of this.

As an aside, the journalists of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists are the good guys, but (Anglo-American) journalism that rejects objectivity is the bigger problem for the question what we can believe in than science.

Fortunately most of the reporting makes clear that the main driving force behind the problem is the publish-or-perish system that politicians and the scientific establishment have set up to micro-manage scientists. If you reward scientists for writing papers rather than doing science, they will write more papers, in the worst case in predatory journals.

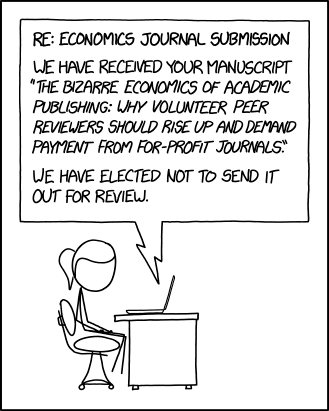

Those in power will likely prefer to make the micromanagement more invasive and prescribe where scientists are allowed to publish. The near monopolistic legacy publishers, who are the only ones really benefiting from this dysfunctional system, will likely lobby in this direction.

Peer review

Many outside of science have unrealistic expectations of peer review and of peer reviewed studies. Peer review is just a filter that improves the average quality of the articles. Science does not deal in certainty (that is religion) and peer reviewed studies certainly do not offer certainty. The claims of single studies (and single scientists) may be better than a random blog post, but reliable scientific understanding should be based on all studies, preferably a few years old, and interpreted by many scientists.This goes much against the mores of the news business, who focus on single studies that are just out, may add some personal interest by portraying single heroic scientists. The news likes spectacular studies that challenge our current understand and are thus the most likely studies to be wrong. If this mess the public sees were science we would not have much scientific progress.

As a consumer of science reporting I would much prefer to read overviews of how the understanding in a certain scientific community is and possibly how it has changed over the last years. It does not have to be recent to be new to me. There is so much I do not know.

the biggest threat to the proper public understanding of science is ... the lie we tell the public (and ourselves) that journal peer review works to separate valid and invalid science

Michael Eisen

Michael Eisen

Peer review is nothing more than that (typically) two independent scientists read the study, give their feedback on things that could be improved and advice the editor on whether the study is sufficiently interesting for the journal in question. Review is not there to detect fraud. Reviewers do not redo all experiments, do not repeat all calculations, do not know every related study that could shine a different light on the results. They just think that other scientists would be interested in reading the article. The main part of the checking, processing of the new information and weaving it into the scientific literature is performed after publication when scientists (try to) build on the work.

The documentary starts with someone with cancer who is conned into a treatment by a scrupulous producer pointing to their peer reviewed studies, partially published in predatory journals. They also criticize that articles from predatory journals were available in a database of a regulatory agency.

However, the treatment in question was not approved and the agency pointed out that they had not used these articles in their assessments. For these assessments scientists come together and discuss the entire literature and how convincing the evidence is in various aspects. These scientists know which journals are reliable, they read the studies and try to understand the situation. One of the interviewed scientists looked at one of the studies on this cancer treatment in a predatory journal and found several reasons why the journal should not have accepted it in the present form.

Also politicians would often like every scientific study to be so perfect that you do not need any expertise to interpret it and can directly use it for regulation. That is not how science works and also not what science was designed for. Science is not an enormous heap of solid facts. Science is a process where scientists gradually understand reality a little better.

Trying to get to the "ideal" of flawless and final studies would make do science much harder. Every scientists would have to be as smart and knowledgeable as the entire community working on something for years. Writing and reviewing scientific article would be so hard that scientific progress would come to a screeching halt. Especially new ideas would have no chance any more.

Conned scientists

Like most scientists I get multiple spam mails a day for fake scientific journals and conferences. Most of them have the quality of Nigerian Prince Spam. People say this kind of spam still exists because the spammers only want really stupid people to respond as they are the easiest to con.Thus I had expected that people who take up such offers know what they are doing. Part of becoming a scientist is learning the publishing landscape of your field. But Open Access publishing reporter Richard Poynder mentioned several cases of scientists being honestly deceived, who tried to reverse their error when they noticed what happened.

The first researcher who contacted me realised something had gone wrong when the manuscript that he and his co-authors had submitted was returned to them with no peer review reports attached and no suggested changes. There was, however, a note to say that it had been accepted, and could they please pay the attached invoice. They later learned that the paper had already been published.Apparently there are also predatory journals with names that are very similar to legitimate ones and a 1% error rate easily happens. I guess assessing the quality of journals can be harder in large fields and in case of interdisciplinary fields. If the first author selects a predatory journal, the co-authors may not have the overview of the journals in the other field to notice the problem.

Quickly realising what had happened, and desperate to recover the situation, the authors agreed to pay the publisher the journal’s full [Author Processing Charges] (over $2,000) – not for publishing their paper, but for taking it down.

We need to find a way help scientists who were honestly fooled and make it possible that the authors can retract their articles themselves. Otherwise they can be held hostage by the predatory publishers, which also funds the organised deception.

If the title of the real article is the same as the one of the predatory article it would be hard to put both on your CV or article list. Real publishers could be a bit more lenient there. A retraction notice of the predatory version in the acknowledgements of the real version should be "shameful" enough that people do not game the system, first publish predatory and then look for a real publisher.

Predators

If there is evidence that scientists purposefully publish in predatory journals or visit fake conferences that should naturally have consequences. That is wasting public money. One institute had 29 publications over a time span of ten years. There is likely a problem there.It should also have consequences when scientists are in the editorial boards of such predatory journals. It may look nice on their CV to be editor, but editors should notice that they are not involved in the peer review or that it is done badly. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that they are aware that they are helping these shady companies. Sometimes these companies put scientists on their editorial boards without asking them. In that case you can expect a scientist to at least state on their homepage that they did not consent.

It is good to see that prosecutors are trying to take down some of these fake publishers. I wish them luck, although I expect this to be hard because it will be difficult to define how good peer review should work. Someone managed to get a paper published with the title "Get me off Your Fucking Mailing List". That would be a clear example of a fail and probably a case of one strike and you are out. At least scientifically, no idea about juridically. With more subtle cases you probably need to demonstrate that this happens more often. Climate "sceptics" occasionally manage to publish enormously bad articles in real scientific journals. That does not immediately make them predatory journals.

Changing publishing

In the past scientific articles were mostly published in paper journals to which academic libraries had subscriptions. This made it hard for the public and many scientists to read scientific articles, especially for scientists from the global South, but I also cannot read articles in one of the journals I publish in regularly myself.Nowadays this system is no longer necessary as journals can be published online. Furthermore, the legacy system is made for monopolies: a reader needs a specific article and an author needs a journal that most scientists subscribe to. As society replaces morality with money and as the publishing industry is concentrating and clearly prioritizes profits over being a good member of the scientific community subscription prices have gone up and service has gone down. As an example of the former, Elsevier has a profit margin of 30 to 50 percent. As an example of the latter, in one journal I unfortunately publish in the manuscript submission system is so complicated that you have to reserve almost a full working day to submit a manuscript.

The hope of the last decade was that a new publishing model would break open the monopoly: open access publishing. In this model articles are free to read and in most cases the authors fund the journals. This reduces the monopoly power of the journals. Readers can read the articles they need and authors can be sure their colleagues can read the article. However, scientists want to publish in journals with a good reputation, which takes years if not decades to build up and still produces a quite strong monopoly situation.

This has resulted in publishing fees of several thousands of Euro for the most prestigious open access journals. In this way these journals are open to read, but no longer open to publish for many researchers. These journals drain a lot of resources that could have been used for research; likely more than the predatory publishers ever will. My guess would be that the current publishing system is 50 to 90 percent too expensive; the predatory journals have less than 1 percent of the market.

The legacy publishers defend their profits and bad service with horror stories about predatory open access journals. They prefer to ignore all the high quality open access journals. This investigative story unfortunately feeds this narrative.

Bad solutions

The Austrian national science foundation (FWF) has found a way to make the situation worse. They want make sure that the scientists they fund will only publish in a list of known good quality open access journals, for example in the Directory of Open Access Journals. That sounds good, but if all science foundations would adopt this policy it would become nearly impossible to start new scientific journals and the monopolies would get stronger again.[UPDATE The German Alliance of Scientific Organizations fortunately states that journal selection is part of the freedom of science. They furthermore state that the quality of a study does not depend on where it is published and want to help scientists with training and information persons. They see a key role for the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).]

I just send a nice manuscript to a new journal, which has no real reputation yet. Its topics fits very well to my work, so I am happy my colleagues started this journal. I did my due diligence, know several people on the editorial board as excellent researchers and even looked through a few published articles. The same publisher has many good journals and journal is by now also listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). The DOAJ was actually very quick and already listed this journal after only publishing 11 articles. But getting those first 11 would be hard if the FWF policy wins out.

The opposite model is to create a black list. This has less problems, but it is quite hard to determine which journals are predatory. There used to be a list of predatory journals by Jeffrey Beall, but he had to stop because of legal threads to his university by the predatory publishers. There were complaints that this list discriminated against journals from developing countries. True or not, this illustrates how hard it is to maintain such a list. There is now, oh irony, a pay-walled version of such a list with predatory journals. The subscriptions should probably pay for the legal risks.

Changing publishing

A good solution would be to review the articles after publication. This would allow researchers to update their assessments when evidence from newer studies come in and we understand the older studies better. PubPeer is a system to do this post-publication peer review, but it mostly has reviews for flawed papers and thus does not give a good overview over the scientific literature.F1000 Prime is an open access journal with post publication review. I know of two more complete post-publication review systems: The Self-Journals of Science and recently Peeriodicals. Here every scientist can start a journal, collect the articles that are worthwhile and write something about them. The more scientists endorse an article, the more influential it is. In these systems I miss reviews of article are not that important, but are valid and they may still be informative for some. Furthermore, I would expect that the review would need to be organized more formally to be seen as worthy successors of the current quality control system.

That is what I am trying to build up at the moment and I have started a first such "grassroots journal" for my own field to show how the system would work. I expect that the system will be superior because these "grassroots journals" do not publish the articles themselves, only review them, and thus can assess all articles in one field at one place, while traditionally articles are spread over many journals. The quality of the reviews will be better because it uses a post-publication review model. The reviews are more helpful to the readers because they are published themselves and quantify in more detail what is good about an article. As such it performs the role of a supervisor in finding one's way in the scientific literature.

You get a similar effect from the always up-to-date review paper on sea surface temperature proposed and executed by my colleagues John Kennedy. This makes it easy for others to contribute, while having versioning and attribution. There is naturally less detail per article that is reviewed.

Changing the system

But also a better reviewing system cannot undo the damage of the fake competitive system currently used to fund scientific research.Volker Epping, president of the University of Hannover, stated: "The pressure to publish is enormous. Problems are inherent to the system." I would even argue: Given the way the system is designed, it is a testament of the dedication of the scientists that it still works so well.

It is called "competitive", but researchers are competing to get their colleagues to approve the funding their research. There is no real competition because there is no real market. If you did a good job, there are no customers that reward you for this. In the best case the rewards come as new funding decided by people who have no skin in the game. People who have no incentive to make good funding decisions. Given that situation, it is amazing that scientists still spend time in making good peer reviews of research proposals and show dedication comparing them with each other to decide what to fund.

My proposal would be to return to the good old days. Give the funding to the universities, which give it to the professors, which allocate it to what they, as the most informed experts, think is interesting research, which furthers their reputation. Professors have skin in the game, their reputation is on the line, and they will invest the limited funds where they expect to get most benefits. In the current system there is no incentive to set priorities, submitting more research proposals has no downsides for them beyond the time it takes to write them. One of the downsides of this model for science is that the best researchers are not doing research, but are writing research proposals.

A compromise could be to limit the number of projects a science foundation funds per laboratory. The Swiss Science Foundation uses this model.

The old and hopefully future system also allows for awarding permanent positions to good researchers. Now most researchers are on short-term contracts because the project funding does not provide stable funding. With these better labour conditions one could attract much better researchers for the same salary.

Because project science requires so many peer reviews (of research proposals and of a bloated number of articles) a lot of time is wasted. (This waste is again much bigger than that of the predatory publishers.) This invites the reviewers to use short-cuts and not assess how good a scientist is and instead assess how many articles they write and how high the prestige is of the journals the articles appear in (bibliometric measures). Officially this system is illegal in Germany, the ethics rules of the German Science Foundation forbid judging researchers and small groups on their bibliometric measures, but it still happens.

My expectation is that without the publish-or-perish system scientific progress would go much faster and we certainly would not have the German public being shocked to learn about predatory publishers.

I hope the affair will inspire journalists to inform the public better on how science works and what peer review is and is not.

Related reading

Investigation of predatory publishing

English summary by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ): New international investigation tackles ‘fake science’ and its poisonous effects.A critical comment in English on the affair: Beyond #FakeScience: How to Overcome Shallow Certainty in Scholarly Communication. With many (mostly German) links to news sources.

The newspaper Indian Express (the Indian partner of the ICIJ): Inside India’s fake research paper shops: pay, publish, profit. Despite UGC blacklist, hundreds of ‘predatory journals’ thrive, cast shadow on quality of faculty and research nationwide.

Comment on the investigation: Predatory Open Access Journals: Is Open Peer Review Any Help? I think it would help, but there are also commercial firms where you can buy peer reviews (next to copy editing, statistical analysis and writing complete articles and theses).

The Bern university library feels criteria for black lists are not transparent and making them puts much power into the hands of a commercial company: On the topic of #predatoryjournals - are there black lists and how reliable are they? In German: Zum Thema #predatoryjournals – gibt es schwarze Listen und wie verlässlich sind sie?

Investigation of scientists of the City University of New York publishing in predatory journals.

Overview of the investigation by the ICIJ in German: Overview of the investigative project in German.

Q&A of ICIJ in German: #FakeScience - Fragen und Antworten.

Why so many researchers use dubious ways to publish (in German). Warum so viele Forscher auf unseriösem Weg publizieren. Volker Epping, president of the University of Hannover: "The pressure to publish is enormous. Problems are inherent to the system." I would even argue: Given the way the system is designed, it is a testament of the dedication of the scientists that it still works so well.

Video of a comment on the affair by Svea-Eckert in German. Like other jouralists, I think she is wrong about the implications.

Peer review

The first grassroots scientific journal, which I hope will inspire the post-publication review system of the future.An always up-to-date review paper by John Kennedy, Elizabeth Kent on GitHub: A review of uncertainty in in situ measurements and data sets of sea-surface temperature. You can use bug reports and pull requests to add to the text.

Separation of feedback, publishing and assessment of scientific studies.

Separation of review powers into feedback and importance assessment could radically improve peer review. Grassroots scientific journals.

Publish or perish is illegal in Germany, for good reason. German science has another tradition, trusting scientists more and focusing on quality. This is expressed in the safeguards for good scientific practice of the German Science Foundation (DFG). It explicitly forbids the use of quantitative assessments of articles.

The value of peer review for science and the press. Is it okay to seek publicity for a work that is not peer reviewed? Should a journalist only write about peer-reviewed studies? Is peer review gate keeping? Is peer review necessary?

Peer review helps fringe ideas gain credibility.

Three cheers for gatekeeping.

Did Isaac Newton Need Peer Review? Scholarly Journals Swear By This Practice of Expert Evaluation. But It’s a New Phenomenon That Isn’t the Only Way To Establish the Facts.

Think. Check. Submit. How to recognise predatory publishers before you submit your work.