Michael Mann responded on Facebook as one of the first scientists. He disliked the "doomist framing" and noted several obvious inaccuracies at the top of the article that all exaggerated the problem.

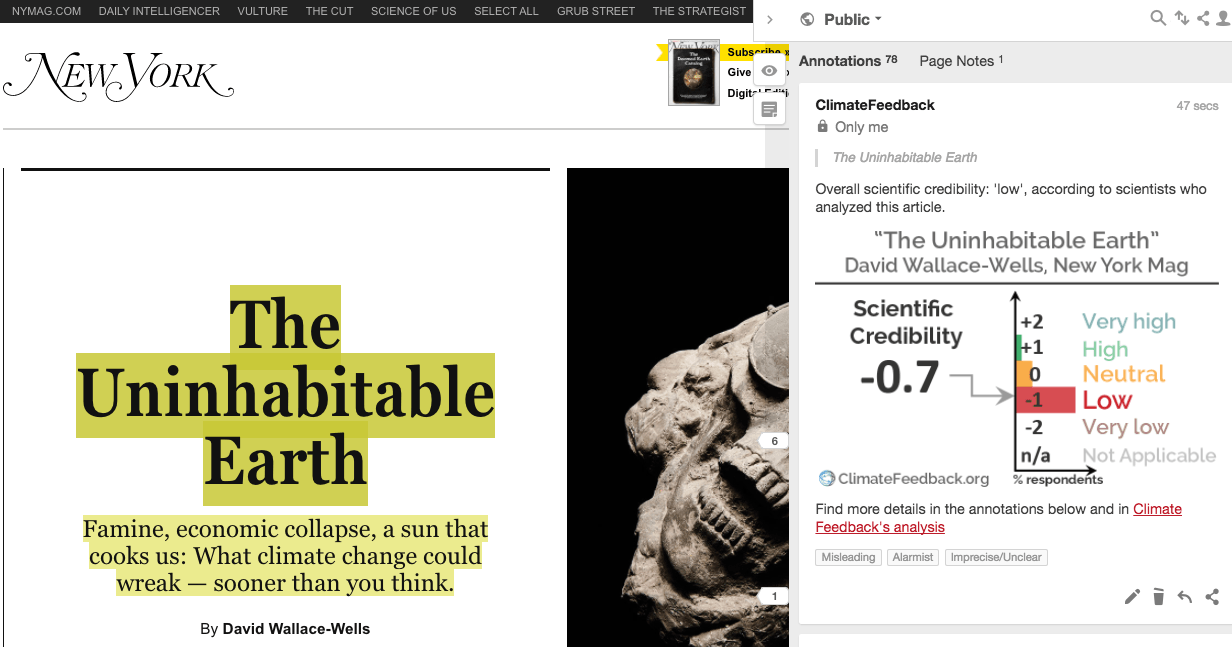

Some days later seventeen climate scientists of Climate Feedback (including me) reviewed the NY Mag article.

In my previous blog post I argued that this is a difficult, but important topic to talk about. The dangers of unfettered climate change are huge. Also if we do not act faster than we did in the past we are taking serious risks with our civilisation and existence. We should seriously consider that the situation can become worse than what we expect on average. Such cases are a big part of the total risk.

While the danger is there and should be discussed, the article contained many inaccuracies, which typically exaggerated the problem. Thus I have rated the article as having "low scientific credibility", which was the most selected rating of the other scientists as well.

Both the critique of Mann and of Climate Feedback produced quite some controversy. This was exceptional; normally the people who see climate change as an important problem trust the scientists who told them about the problem.

Like other climate scientists I correct both sides when I see something and have enough expertise. Although it is much rarer to have to correct people who see climate change as a problem (let's call them the "concerned"). I guess the real problem is big enough, there is not much need to exaggerate it. The overwhelming amount of nonsense comes from people playing down the problem. Normally the deniers really dislike contrary evidence, but the concerned are mostly happy to be corrected and to be able see the problem more clearly.

It is interesting that this time the corrections were much more controversial. Why was it different this time? Was our "nitpicking" a case of the science police striking again? Could Climate Feedback give more useful ratings?

Doomsday scenarios are as harmful as climate change denial

Michael Mann followed up his Facebook post with an article in the Washington Post together with communication expert Susan Joy Hassol that "doomsday scenarios are as harmful as climate change denial". The key argument was:Some seem to think that people need to be shocked and frightened to get them to engage with climate change. But research shows that the most motivating emotions are worry, interest and hope. Importantly, fear does not motivate, and appealing to it is often counter-productive as it tends to distance people from the problem, leading them to disengage, doubt and even dismiss it.This is an argument climate activists who want to be effective need to be aware of. The well-known groups already tend to stick to the science. Climate change is bad enough as it is and they rightly value their credibility.

The argument makes me uncomfortable, however, when connected to science. The situation is what it is. Also if that provokes fear, scientists should stick to the evidence and not tone it down to be "effective". It is the job of an activist to be effective. It is our job is to be honest.

If the population would have to fear we are not honest, that would produce additional uncertainty and give more room for the prophets of doom. Thus toning it down fearing fear can also produce fear.

David Wallace-Wells uses the fear that scientists hide the severity to make his story more scary. He is claiming throughout that article that scientists are not giving it straight: scientist are technocrats who are too optimistic that the problem can be solved, "climate denialism has made scientists even more cautious", he talked to many scientists, but does not name most in the original article, thus suggesting they are only willing to tell the truth anonymously, "the many sober-minded scientists I interviewed over the past several months ... have quietly reached an apocalyptic conclusion", "Pollyannaish plant physiologists", "Climatologists are very careful when talking about Syria", "But climate scientists have a strange kind of faith: We will find a way to forestall radical warming, they say, because we must."

This framing may have made the article more attractive to readers who expect scientists not to be honest and to understate the problems. This in turn may have provoked a more allergic reaction to the Climate Feedback critique than an article mostly read by people who love and respect science.

That the audience matters is also suggested by clear difference in the responses on Reddit sceptic and Reddit Collapse. The people on the Reddit of the real sceptics (not the fake climate "sceptics") were interested, while the people preparing for the collapse of civilisation were more often unhappy about Climate Feedback.

In the Climate Feedback reviews the doomist tone is often not appreciated, but if you look at the details, at the annotations of the scientists, it is clear that the problem is that the NY Mag article contains errors that exaggerate the problem, not the bad news that is accurate. In the summaries spreading doom and exaggerating were sometimes used interchangeably. So let me say clearly: I have never talked to a scientists who was more worried in private than in public.

While scientists say what they think, they do tend to be careful in what they claim. The more careful the claim, the more confident a scientist can be that the evidence is sufficient to support it. We like strong and thus careful claims. This is justified when it comes to the question whether there is a problem. You do not want to cry wolf too often when there is none. However, as I have argued on this blog before we should not be careful about the size of the wolf. Saying the wolf is a Chihuahua is not good advice to the public.

My advice to the public would be to expect problems to be somewhat worse than the scientific mainstream claims, but not to go to prophets of doom and especially to avoid sources with a history of inaccurate information. (At least for mature problems, in case of fresh problem it can go both ways.)

Nitpicking

Looking at the high risk tails is uncomfortable for everyone, also for scientists. That provokes more critical reading and an unfortunate claim in such a story will get more comments than a similar one hidden in a middle of the road most accurate story.However, unfortunately the article also often made statements are clearly inaccurate, wrong or are missing important context. The biggest error in the article — from my perspective as someone who works on how accurately we know how much the Earth is warming — was this line:

there are alarming stories every day, like last month’s satellite data showing the globe warming, since 1998, more than twice as fast as scientists had thought.This has been updated by David Wallace-Wells to now read:

there are alarming stories in the news every day, like those, last month, that seemed to suggest satellite data showed the globe warming since 1998 more than twice as fast as scientists had thought (in fact, the underlying story was considerably less alarming than the headlines).This was a report on a satellite upper air dataset that was the favourite of the climate "sceptics" because it showed the laast warming. Scientists have always warmed that that dataset was unreliable. Now an update has brought it in line with the other temperature datasets. The "twice as fast" is just for a cherry picked period. That is about as bad as mitigation sceptical claiming that global warming has stopped by cherry picking a specific period.

The scientific assessment for the actual warming did not change, certainly not become twice as much. If anything we now understand the problem better, which would mean less risk. The change is also not that much compared to the warming we had over the last century.

Because the actual scientific assessment did not change one could also argue that the mistake is inconsequential for the main argument of the story and the comment thus nitpicking. At least for me it matters. I hope more people feel this way.

There were many more mistakes like this and cases where missing context will give the reader the wrong impression. I do not want to go through them all in this already long post; you can read the annotations.

There were also cases which were also nitpicking from a scientific viewpoint. Where these comments were mine, I included them for completeness. They also did not influence my rating much.

Apparently I have to add that parts of the text without annotations are not automatically accurate. Especially for such a long article annotating is a lot of work. At a certain moment there are enough annotations to make an assessment. In addition even with 17 scientists it will happen that none of the scientists has relevant expertise for specific claims.

Climate Feedback rating system

We may want to have another look at the rating system used by Climate Feedback; see below. Normally finding a grade is quite straight forward. In this case I had to think long and was still not really satisfied.Suggested guidelines for the overall scientific credibility rating

Remember that we do not evaluate the opinion of the author, but instead the scientific accuracy of facts contained within the text, and the scientific quality of reasoning used.

- +2 = Very High: No inaccuracies, fairly represents the state of scientific knowledge, well argumented and documented, references are provided for key elements. The article provides insights to the reader about climate change mechanisms and implications.

- +1 = High: The article does not contain major scientific inaccuracies and its conclusion follows from the evidence provided.

- 0 = Neutral: No major inaccuracies, but no important insight to better explain implications of the science.

- -1 = Low: The article contains significant scientific inaccuracies or misleading statements.

- -2 = Very Low: The article contains major scientific inaccuracies for key facts supporting the author’s argumentation and/or omits to mention important information and/or presents logical flaws in using information to reach his or her conclusion.

- n/a = Not Applicable: The article does not build on scientifically verifiable information (e.g., it is mostly about politics or opinions).

The scale is not symmetrical in the sense that if you get X facts wrong and X facts right you are in the middle. It might be that some people expect that. I would argue that getting only 50% right is pretty bad for a science article.

A problem in this case was that we can only give integer grades. So I gave a -1. I thought about neutral, but decided against it because that would mean "no major inaccuracies" and there were. For the part I could judge I found several mistakes and cases of missing important context (that is the description of -1). Had it been possible, I would have given the article a -0.5., because the tag "low scientific credibility" sounds a bit too harsh.

The rating of the article and the summary is made independently by all scientists and most made the same consideration. Had I been able to see the other "low" rating, I might have opted for "neutral" for balance. (We can see the annotations of the other scientists and can also respond to them. Sometimes when I am one of the first to make annotations, I wait with my rating to see what problems the others find.)

The relativity of wrong is very important. This same week Climate Feedback reviewed a Breitbart story about the accuracy of the instrumental warming estimate (my blog post on it). That was a complete con job and got "very low" rating. Giving the New York Magazine piece half the Breitbart rating does nor feel right. A scale from 0 to 4 may work better than one from -2 to 2. A zero sounds a lot worse than one and "low" would not be half of "very low".

The actual problem may be only -2 means inaccuracies influencing the main line of the story. It is more a scale for a science nerd looking for a high quality article than a scale for a citizen wanting to know how reliable the main line of the story is. Up to now that was mostly correlated, for this piece is was not, which made grading hard.

The more concrete a claim is, the more objective it can be assessed. Thus I would personally prefer to keep it a scale for science nerds and not go to a more vague and subjective assessment whether the main line is accurate.

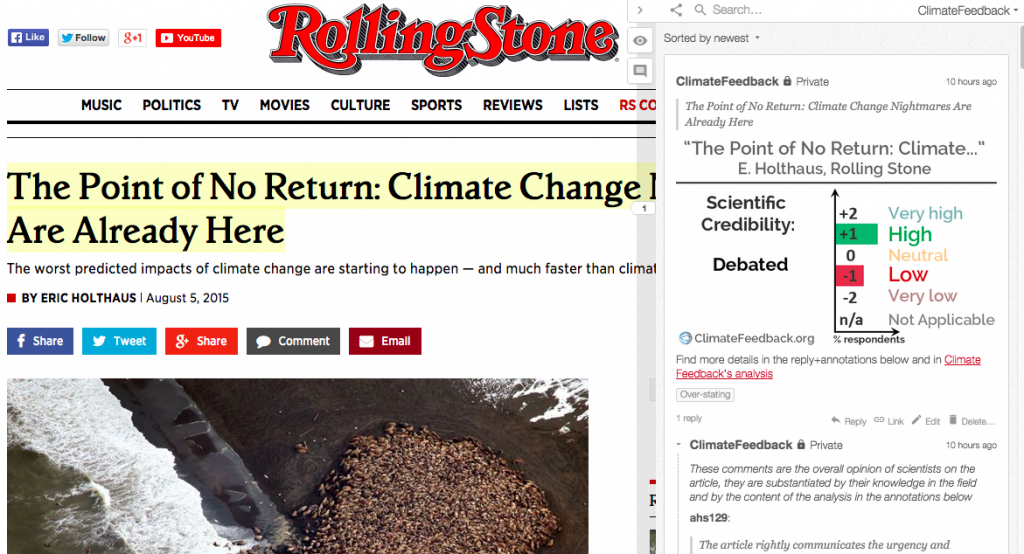

A previous Feedback on a climate nightmare article by climate journalist Eric Holthaus got plus and minus ones. That shows that such an article can get positive ratings. That the article was never rated "neural" suggests that we may have to reconsider its description. That it states "no important insight" may make neutral almost worse than -1. It sounds like the famous quote: "not even wrong."

Based on the above discussion of the NY Mag review my suggestion for a new rating system would be the one below. It should be seen if it also fits well to other articles. I changed the numbers, the short descriptions and the long description for neutral.

Suggested guidelines for the overall scientific credibility rating

Remember that we do not evaluate the opinion of the author, but instead the scientific accuracy of facts contained within the text, and the scientific quality of reasoning used.

- 4 = Excellent science reporting: No inaccuracies, fairly represents the state of scientific knowledge, well argumented and documented, references are provided for key elements. The article provides insights to the reader about climate change mechanisms and implications.

- 3 = Very good science reporting: The article does not contain major scientific inaccuracies and its conclusion follows from the evidence provided.

- 2 = Good science reporting: Mostly accurate statements and only minor inaccurate ones.

- 1 = Some problems: The article contains significant scientific inaccuracies or misleading statements.

- 0 = Major errors: The article contains major scientific inaccuracies for key facts supporting the author’s argumentation and/or omits to mention important information and/or presents logical flaws in using information to reach his or her conclusion.

- n/a = Not Applicable: The article does not build on scientifically verifiable information (e.g., it is mostly about politics or opinions).

Why climate feedback?

There were people asking why we, Climate Feedback, were doing this. This could be interpreted in two ways:1) Why do you nitpick this article I feel is an important wake-up call?

2) Why do you do this at all?

First of all, we do not know in advance what the outcome will be. Many articles on climate change are also very good and get great ratings. That is the kind of feedback journalists appreciate and which may help them in their careers and stimulate them to write better articles. Some journalists have even asked for reviews of important pieces to showcase the quality of their work.

We had a few authors who updated their article. David Wallace-Wells also did so and added more sources and transcripts. As far as I know such updates have only happened on the side that accepts the science. Also in that way our work improves science journalism, although such updates will come too late for most readers.

The reviews have already made clear that people who accept that climate change is real typically write accurate articles, while writers who do not want to solve the problem typically write error-ridden and misleading articles. That is good to know.

Only criticising the climate "sceptics" is not in the nature and in the training of good scientists. More utilitarian: solving climate change is a marathon, the energy transition will not be completed before 2050. Adaptation to limit the consequences of climate change will also be a job for generations to come. It is thus important that scientists are seen as trustworthy and only picking on one group would damage our reputation.

There are people who want to understand the details and when they meet misinformation being able to explain what is wrong with it. On reddit these people gather in /r/skeptic/. They normally accept climate change is real and like details/nitpicking, quality arguments and a rational world.

29. Along comes a brilliant writer from outside those circles, w/ a galvanizing, wildly popular piece, & for his efforts, he is ... scolded.— David Roberts (@drvox) 12 July 2017

I do worry that there is also a downside to science policing in that people are less comfortable speaking about climate change fearing to be corrected. That is one reason to let minor cases slip and in bigger cases be gracious when it is the first time making a mistake. David Wallace-Wells responded graciously to the critiques, it were others that objected.

Making a mistake is completely different from the industrial production of nonsense on WUWT & Co.

It would be progress if scientists had a smaller role in this weird US "debate". It was forced on us by a continual stream of misinformation on the science from climate "sceptics". There should be a debate what to do about it and that is a debate for everyone. If you would see less scientists in US debates around climate change that would probably mean that the important questions are finally being addressed.

It would also be progress because scientists are typically not very good communicators. Partially that is because most scientists are introverted. Partially that is the nature of the problem, some things are simply not true, some arguments are simply not valid and there is little room for negotiation and graciousness.

On the other hand, science communication works pretty well in countries without the systemic corruption in Washington and the US media. So I do not think scientists are the main problem.

Related reading

Part I of this blog series: "How to talk about climate doomsday scenarios."The updated New York Magazine piece By David Wallace-Wells: The Uninhabitable Earth - Famine, economic collapse, a sun that cooks us: What climate change could wreak — sooner than you think. (The reviewed original, the version with annotations.)

The Climate Feedback Feedback: Scientists explain what New York Magazine article on “The Uninhabitable Earth” gets wrong.

New York Magazine now also published extended interviews with the scientists interviewed for the piece: James Hansen, Peter Ward, Walley Broker, Michael Mann, and Michael Oppenheimer.

Introduction to Climate Feedback: Climate scientists are now grading climate journalism