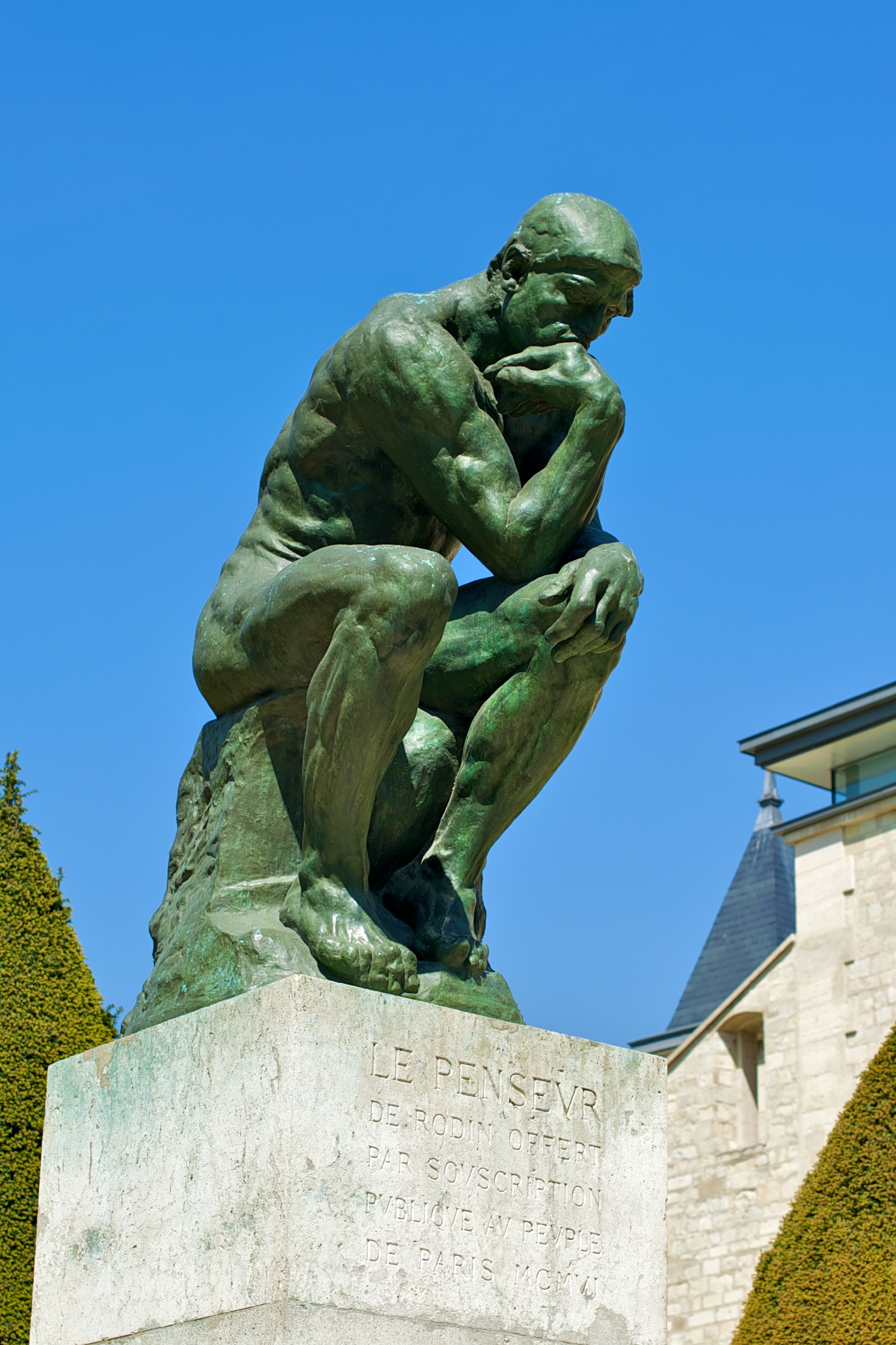

The grave of Isaac Newton. Newton made himself vulnerable, wrote up his mechanics and optics very clearly. So that it could be falsified and was falsified. While he never repented his errors in public on facebook, his erroneous work did science a great service.

Being shown to be wrong is not nice. That could be one of the reasons why science is a very recent invention, it does not come to humans easily.

Being shown wrong is central, however, to scientific progress.

Being trivially wrong, of the kind displayed on WUWT every day, does not help science and is very bad for your scientific reputation.

Being wrong in an interesting way is scientific progress. The moment someone shows why you were interestingly wrong, we understand the problem a little better. If you can make your colleagues think and understand things better, that is good. Like Albert Einstein who was wrong about quantum mechanics until he died, but his challenges were interested and enhance his reputation.

Because it is hard to make yourself vulnerable, because it is good for science when you do so, because it is good for science when others show you wrong, the scientific community has a culture that encourages people to be bold and allows them to be wrong in an interesting way. If scientists would receive a hostile fit every time someone shows them wrong, that would not encourage them much to contribute to scientific understanding.

language

It starts with the language. Instead of saying someone was wrong, scientists talk about "progressive insight". Actually, it is a bit more than just language, often scientists really could not have known that they were wrong because some experiment or observation had not been made yet. Often this observation was inspired by their ideas. Often "progressive insight" also an argument that was overlooked and could theoretically have been thought up before. You could call that being wrong, but "progressive insight" is much more helpful.Such a change of language is apparently also important in eduction. A high school teacher wrote:

One of the biggest challenges is convincing teenagers that they can be wrong about anything, let alone that there's value in it, ... Therefore, a few weeks ago I assigned my 90 or so Freshmen the task of keeping a 9-week Surprise Journal. ...[[Nassim Taleb]], who wrote The Black Swan, mentioned that it is easier for Arabs to admit they do not know something, which is much better than pretending you do, because they express this by saying: only God knows. Much more neutral. (It is highly recommended for anyone in the climate "debate" to read one of his books on new and unpredictable risks and human tendencies to be blind to chance.)

I've noticed something, well, surprising. In the class culture, acknowledgement that you are mistaken about something has become dubbed a "moment of surprise" (followed by a student scrambling to retrieve their Journal to record it). As this is much more value neutral than "I screwed up," the atmosphere surrounding the topic is less stressful than in previous years (I suspect -- based on anecdotal evidence -- that they have a history of being punished for mistakes and so are justifiably skittish about the whole topic). That by itself makes me inclined to judge this experiment a success, and has already added richness to our subsequent activities and discussions...

This amicable scientific culture is also the reason that scientific articles are clear on the work performed, but very subtle in pointing our problems with previous studies, to the extent that sometimes only an expert can even notice that a previous study was criticized.

A less subtle example of trying to be amicable would be the article that made me "famous". A study comparing the skill of almost all homogenization method used to remove non-climatic changes. In the tables you can find the numbers showing which method performed how well. In the text we only recommended the application of the five best methods and did not write much about the less good ones. The reader is smart enough to make that connection himself.

At conferences I do explicitly state that some methods should better not be used any more. In private conversions I may be even more blunt. I feel this is a good general rule in life: praise people in writing, so that they can read it over and over again, criticize people in person, so that is can be forgotten again and you can judge whether the message had the right impact and is well understood. Easier said than done; the other way around is easier.

The bar between a stupid error and an interesting one goes up during the process. In a brainstorm with your close colleagues, you should be able to mention any idea, a stupid idea may inspire someone else to find a better one. At an internal talk about a new idea, it is okay if some peers or seniors notice the problem. If all peers or too many juniors see the problem, your reputation may suffer.

Similarly, if all people at a workshop see the problem, your reputation takes a hit, but if only one sees it. If someone from another field, who has knowledge that you do not, that should not be a problem; that is what conferences are for, to get feedback from people with other backgrounds. Only few people heard it, it will normally not be sufficiently important to talk about that with people who were not present and the mistake will be quickly forgotten. Like it should, if you want to encourage scientists taking risks.

There is a limit to this amicable culture. Making trivial mistakes hurts your reputation. Making again them after being been shown wrong hurts your reputation even more. Being regularly trivially wrong is where the fun stops. There is no excuse for doing bad science. Quality matters and do not let any mitigation skeptics tell you that they are attacked for the political implications of their work, it is the quality. I am very critical of homogenization and doubt studies on changes in extremes from daily station data, but I have good arguments for it and being skeptical certainly did not hurt me, on the contrary.

The difference between writing text, fixed for eternity, open for critique forever, and spoken language is also the reason why I am not too enthusiastic about tweeting conferences. On the other hand, to reduce travel it would be a nice if the talks of conferences were broadcasted over the internet. To reduce the tension between these two requirements maybe we could make something like [[snapchat]] for scientific talks. You can only look at it once (in the week of the conference) and then the video is deleted forever.

The above is the ideal case. Scientists are also humans. Especially when people keep on making similar wrong claims, when you can no longer speak about mistakes, but really about problems, also scientists can become less friendly. One case where I could understand this well was during a conference about long range dependence. This term is defined in such a vague way that you can not show that a signal does not have it. Thus a colleague asked whether a PhD student working on this had read Karl Popper? His professor answered: "First of all you have to believe in long range dependence."

For scientific progress it is not necessary for scientists to publicly pronounce that the denounce their old work. It is more than sufficient that they reference the new work (which without critique is interpreted as signalling that the reference is worth reading), that they adopt the new ideas, use the new methods and again build on them. The situation is also normally not that clear, scientific progress is a continual "negotiation" process while evidence is gathered. Once the dust settles and the evidence is clear, it would be trivial and silly to ask for a denouncement.

Calls for walks to walks to Canossa only hinder scientific progress.

politics

In politics the situation is different. If politically helpful, the opponent changing his or her mind is put in a bad light and is called flip-flopping. If someone once made a mistake, very unhelpful calls for public retractions, repentance and walks to [[Canossa]] are made. Anything to humiliate the political opponent. Politics does not have to be this way, when I was young politicians in The Netherlands still made an effort to understand and convince each other. As sovereigns we should encourage this and reward it with our votes.A funny example in the political climate "debate" is that the mitigation skeptic FoxGoose thought the could smear BBD by revealing the BBD had once changed his mind, that BBD was once a mitigation skeptic. He had not counted on the reaction of more scientifically minded people, who praised BBD for his strength to admit having been wrong and to leave the building of lies.

I discovered that I was being lied to. This simply by comparing the “sceptic” narrative with the standard version. Unlike my fellow “sceptics” I was still just barely sceptical enough (though sunk in denial) to check both versions. Once I realised what was going on, that was the end of BBD the lukewarmer (NB: I was never so far gone as to deny the basic physics, only to pretend that S [the climate sensitivity] was very low). All horribly embarrassing now, of course, but you live and learn. Or at least, some of us do. ...Mitigation skeptics sometimes state something along the lines: I would believe climate scientists if only they would denounce the hockey stick of Michael Mann as a hoax. Firstly, I simply do not believe this. The mitigation skeptics form a political movement. When mitigation skeptics do not even tell their peers that it is nonsense to deny that the CO2 increases are man made, they signal that politics is more important to them than science. For the worst transgressions at WUWT you will sometimes see people complaining that that will make their movement look bad. Such a strategic argument is probably the strongest argument to make at WUWT, but the right reason to reject nonsense is because it is nonsense.

Always check. Fail to do this in business and you will end up bankrupt and in the courts. I failed to check, at least initially, and made a colossal prat out of myself. Oh, and never underestimate the power of denial (aka ‘wishful thinking’). It’s brought down better people than me. ...

There wasn’t a single, defining eureka moment, just a growing sense of unease because nothing seemed to add up. ... Once I eventually started to compare WUWT [Watts Up With That] with RC [RealClimate] and SkS [Skeptical Science], that was it, really.

Secondly, the call to denounce past science also ignores that methods to compute past temperatures have progressed, which is an implicit sign that past methods could naturally be improved. An explicit denouncement would not change the science. To keep on making scientific progress, we should keep the scientific culture of mild indirect criticism alive. The disgusting political attack on science in the USA are part of their cultural wars and should be solved by the Americans. That is not reason to change science. Maybe the Americans could start by simply talking to each other and noticing how much they have in common. Stopping to consume hateful radio, TV and blogs will make the quality your life a lot better.

Let me close with a beautiful analogy by Tom Curtis:

We do not consider the Wright brothers efforts as shoddy because their engines were under powered, their planes flimsy, and their controls rudimentary. To do so would be to forget where they stand in the history of aviation – to apply standards to pioneers that develop on the basis of mature knowledge and experience in the field. Everybody including Michael Mann is certain that, with hindsight, there are things MBH98 could have done better – but we only have that hindsight because they did it first. So, the proper gloss is not “shoddy”, but pioneering.

Tweet

Related reading

Are debatable scientific questions debatable?On the difference between scientific disputes and political debates.

Falsifiable and falsification in science

Scientific theories need to be falsifiable. Falsification is not trivial, however, and a perceived discrepancy a reason for further study to get a better understanding, not for a rejection of everything. That is politics.

How climatology treats sceptics

I have been very critical of homogenization. I had good arguments and was royally rewarded for my skepticism. The skeptics that cry persecution may want to have a second look at the quality of their "arguments".

Scientific meetings. The freedom to tweet and the freedom not to be tweeted

Stop all harassment of all scientists now

Climatology is a mature field

* Top photo of Newtons grave from Wikimedia is in the public domain.