1. Fuzzy definition

One reason is that the consensus is hard to define. To the above informal statement I could have added, that greenhouse gasses warm the Earth's surface, that CO2 is a greenhouse gas, that the increase in the atmospheric CO2 concentration is mainly due to human causes, and so on. That would not have changed much and also the fraction of scientists supporting this new definition would be about the same.You could probably also add some consequences, such as sea level rise or stronger precipitation, without much changes. However, if you would start to quantify and ask about a certain range for the climate sensitivity or add some consequences that are harder to predict, such as more drought, stronger extreme precipitation, the consensus will likely become smaller, especially as more and more scientists will feel unable to answer with confidence.

Whether there is a consensus on X or not is a question about humans. Such social science questions will always be more fuzzy as questions in the natural sciences. I guess we will just have to live with that. Just because concepts are a bit fuzzy, does not mean that it does not make sense to talk about them. If you think some aspect of this fuzziness creates problems, you can do the research to show this.

2. Scientific culture

By defining a consensus and by quantifying its support, you create two groups of scientists, mainstream and fringe. This does not fit to the culture in the scientific community to keep communication channels open to all scientists and not to exclude anyone.Naturally, also in science, as a human enterprise, you have coalitions, but we do our best to diffuse them and even in the worst case, there are normally people on speaking terms with multiple coalitions.

However, also without its quantification, the consensus exists. Thus communicating it does not make that much difference. The best antidote is for scientists to do their best to keep the lines of communication open. A colleague of mine who does great work on the homogenization thinks global warming is a NATO conspiracy. My previous boss was a climate "sceptic". Both nice people and being scientists they are able to talk about their dissent in a friendlier tone as WUWT and Co.

3. Evidence

Many people, and maybe also some scientists, may confuse consensus with evidence. For a scientist referring to a consensus is not an option in his own area of expertise. Saying "everyone believes this" is not a scientific argument.Consensus does provide some guidance and signal credibility, especially on topics where it is easily possible to test an idea. If I had a new idea and it would require an exceptionally high or low amount of future sea level rise, I would probably not worry too much as there is not much consensus yet on these predictions and I would read this literature and see if it is possible to make matters fit somehow. If my new idea would require the greenhouse effect to be wrong, I would first try to find the error in my idea, given the strong consensus, the straight forward physics and clear experimental confirmation it would be very surprising if the greenhouse theory would be wrong.

For scientists or interested people knowing there is a consensus is not enough. Fortunately, in the climate sciences the evidence is summarised every well in the IPCC reports.

The weight of the evidence clearly matters: The consensus in the nutritional sciences seems to be that you need to move more and eat less, especially eat less fat, to lose weight. As far as I can judge this is based on rather weak evidence. Finding hard evidence on nutrition is difficult, human bodies are highly complex, finding physical mechanisms is thus nearly impossible. The bodies of ice bears (eating lots of fat), lions (eating lots of protein) and gazelles (eating lots of carbs) are very similar. They all have arteries and the ice bears arteries do not get clogged by fat; they all have kidneys and the lions kidneys can process the protein and their bones do not melt away; they all have insulin, but the gazelles do not get diabetes or obesity from all those carbs. Traditional humans ate a similar range of diets without the chronic deceases we have seen the last generations. Also experiments with humans are difficult, especially when it comes to chronic decease where experiments would have to run over generations. Most findings on diet are thus based on observational studies, which can generate interesting hypotheses, but little hard evidence. It would be great if the nutritional sciences also wrote an IPCC-like report.

For a normal person, I find it completely acceptable to say, I hold this view because most of the worlds scientists agree. I did so for a long time on diet, while I now found that the standard approach does not work for me, I feel it was rational to listen to the experts as long as I did not study the topic myself. It is impossible to be an expert for every topic. In such cases the scientific consensus is a good guiding light and communicating it is valuable, especially if a large part of the population claims not to be aware of it.

4. Contrarians

The concept "consensus" is in itself uncomfortable to many scientists. Most of us are natural contrarians and our job is to make the next consensus, not to defend the old one. Even if our studies end up validating a theory, the hope and aim of a validation study is to find an interesting deviation, that may be he beginning of a new understanding.Given this mindset and these aims, many scientists may not notice the value of consensus theories and methods. They are what we learn during our studies. When we read scientific articles we notice on which topics there is consensus and on which there is not. When you do something new, you cannot change everything at once. Ideally a new work can be woven into the network of the other consensus ideas to become the new consensus. If this is not possible yet, there will likely be a period without consensus on that topic. If there is no consensus on a certain topic, that is a clear indication that there is work to do (if the topic is important).

5. Scientific literature

A final aspect that could be troubling is that the consensus studies were published in the scientific literature. It is a good principle to keep the political climate "debate" out of science and thus out of the scientific literature as well as possible. It is hard enough to do so. Climate dissenters regularly game the system and try to get their stuff published in the scientific literature. Peer review is not perfect and some bad manuscripts can unfortunately slip through.One could see the publication of a consensus study as a similar attempt to exploit the scientific literature. Given that all climate scientists are already aware of the consensus, such a study does not seem to be a scientific urgency. Furthermore, Dana Nuccitelli acknowledged that one of the many aims was to make "the public more aware of the consensus".

However, many social scientists do not seem to be aware of the consensus and feel justified to see blogs such as WUWT as a contribution to a scientific debate, rather than as the political blog it is, that only pretends to be about science. One of the first consensus studies was even published in the prestigious broadly read journal Science. Replications of such a study, especially if done in another or better way seem worth publishing. The large difference in the perception of the consensus on climate change between the public and climate scientists is worth studying and these consensus studies provide an important data point to estimate this difference.

Just because the result sounds like a no-brainer is no reason not to study this and confirm the idea. Not too long ago a German newspaper reported on a study whether eating breakfast was good for weight loss. A large fraction of the comments were furious that such an obvious result had been studied with public money. I must admit, that I no longer know whether the obvious result was that if you do not eat breakfast (like Italians) you eat less and thus lose weight or whether people that eat breakfast (like Germans) are less hungry and thus compensate this by eating less during the rest of the day. I think, they did find an effect, thus the obvious result was not that it naturally does not matter when you eat.

As a natural scientist, it is hard for me to judge how much these studies contribute to the social sciences. That should be the criterion. Whether an additional aim is to educate the public seems irrelevant to me. The papers were published in journals with a broad range of topics. If there were no interest from the social science, I would prefer to write up these studies in a normal report, just like an Gallop poll. However, my estimate as outsider would be that these paper are scientifically interesting for the social sciences.

Outside of science

An important political strategy to delay action on climate is to claim that the science is not settled, that there is no consensus yet. The infamous Luntz memo from 2002 to the US Republican president stated:Voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming within the scientific community. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debateThis is important because the population places much trust in science. Thus holding that trust and the view that there is no climate change must produce considerable cognitive dissonance.

There is a consensus within the Tea Party Conservatives that human caused climate change does not exist. It is naturally inconvenient for them that this is wrong. However, I did not make up this escapist ideology. Thus for me as a scientist this is not reason to lie about the existence of a clear consensus about and strong evidence for the basics of climate change. Even if that were a bad communication strategy, which I do not believe, my role as a scientist is to speak the truth.

What do you think? Did I miss any reason why a scientist might not like the consensus concept? Or an argument why these reasons are weak if you think about it a bit longer? I will not post comments with flimsy evidence against The Consensus Project. You can do that elsewhere where people are more tolerant and already know the counter arguments by heart.

[Update, 23 Sept 2014. This post is now linked on Spiegel Online, where the local climate "skeptic" Axel Bojanowski needs no act as if I agree with him. I admit that the title suggests this, I was hoping to get a few "sceptics" to read it, but I was hoping that people reading the post itself would see that every single "reason" is countered. Thus Bojanowski was cherry picking, I hope it was not on purpose, but just by not reading carefully.

Axel Bojanowski calls the topic of the Cook et al. study a "banality". Because even the most hardened skeptics of the climate research do not doubt the physical basis that greenhouse gasses from cars, factories and power plants heat the atmosphere. (Selbst hartgesottene Kritiker der Klimaforschung zweifeln nicht an dem physikalischen Grundsatz, dass Treibhausgase aus Autos, Fabriken und Kraftwerken die Luft wärmen.) It would unfortunately be a great jump forward if Bojanowski was right.

The blog Global Warming Solved lists 16 people/blogs that agree with them that climate change is not man-made. In this list are well known people/blogs from the "skeptic" community: Roger “Tallbloke” Tattersall, The Hockey Schtick (often cited at WUWT), the German blog No Tricks Zone (Pierre Gosselin, who is followed by Bojanowski on twitter), Tom Nelson, Climate Depot (Mark Morano; CFACT), Steven Goddard, James Delingpole, Luboš Motl, and Tim Ball (regularly posts on WUWT).

Roy Spencer recently wrote a post with the "Skeptical Arguments that Don’t Hold Water". Most of which were somehow acknowledging that CO2 is a greenhouse gas, that was the biggest concession he was willing to make. He realized that even this was controversial in his community and wrote in the intro:

My obvious goal here is not to change minds that are already made up, which is impossible (by definition), but to reach 1,000+ (mostly nasty) comments in response to this post. So, help me out here!He got "only" 700 comments, but the tendency was as expected.

At the main Australian climate skeptic blog, I once pointed out that even the host, Jo Nova, accepts that CO2 is a greenhouse gas. That produced a lively push back and no one came forward to say that naturally CO2 is a greenhouse gas.

I can only conclude that some "high profile" "sceptic" bloggers pay lip service to accepting that global warming is man-made (while many of their posts do not make sense if they would). And that at least a large part of their audiences is against accepting any scientific fact that is accepted by liberals. ]

Tweet

Related reading

In case you do not like people judging abstracts, there are also surveys of the opinion of climate scientists. For example this survey by the people behind the Klimazwiebel.Andy Skuce responds to critique of consensus study in his post: Consensus, Criticism, Communication and gives a nice overview of the various possible critiques and why they do not hold water.

On consensus and dissent in science - consensus signals credibility

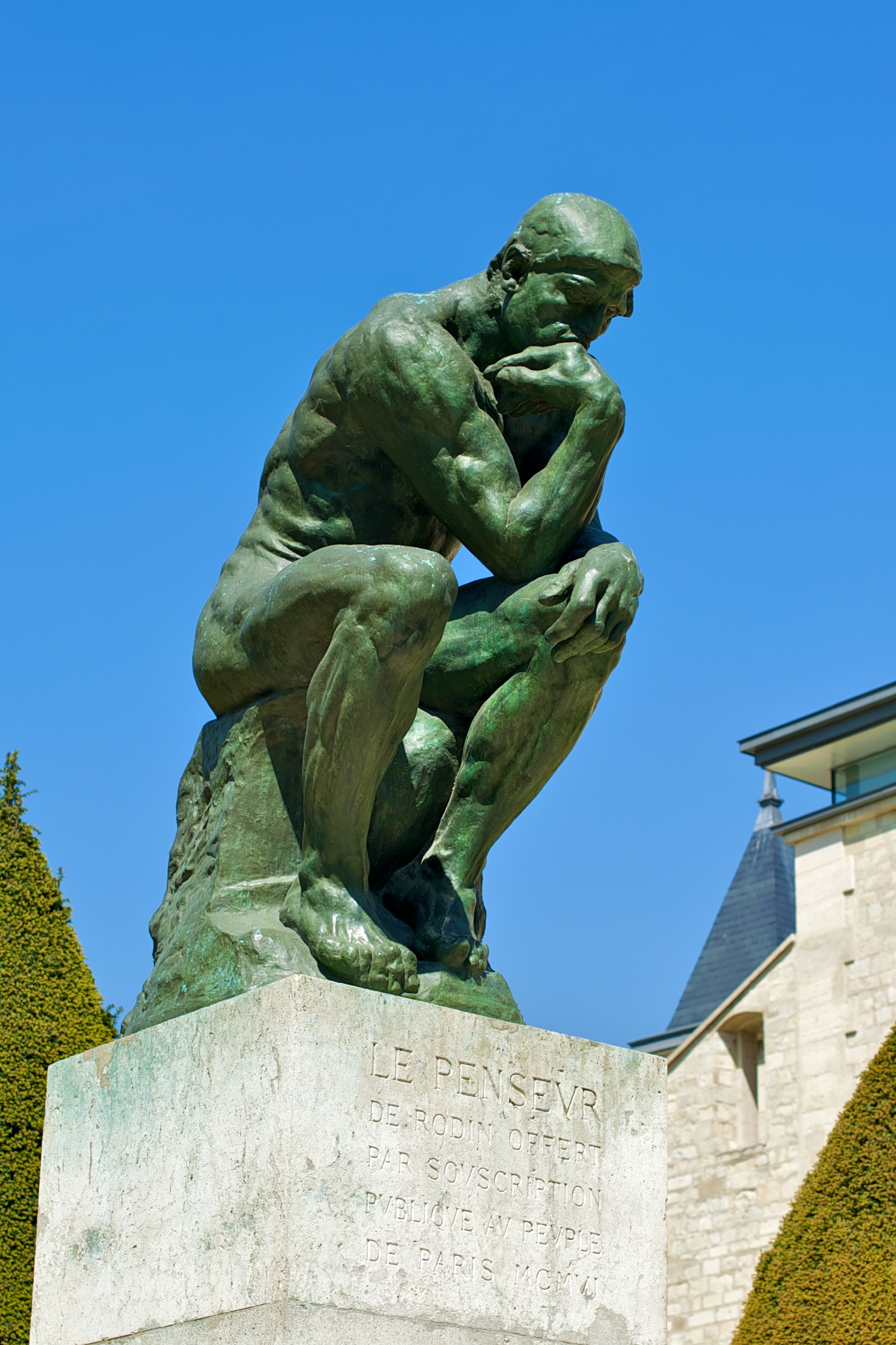

Photo: „Paris 2010 - Le Penseur“ by Daniel Stockman - Flickr: Paris 2010 Day 3 - 9. Licensed with CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.